- adjective

An adjective is a part of speech used to describe something, which usually goes with a noun or noun phrase, giving more information about the object signified.

English examples include big, good, red, Australian, expensive, wooden, quick.

In English, adjectives usually go before the noun they modify (e.g., a big rock) and there is a certain order in which they should go (e.g., you can’t say *a red big rock).

Other languages have different rules, like where the adjective goes in relation to the noun it modifies, or what order the adjectives go in. Some languages only have a few adjectives.

Don’t assume that the rules for adjectives in another language are the same as in English.

- adverb

An adverb is a word or phrase that modifies the meaning of an adjective, verb, or another adverb.

Adverbs typically express manner, place, time, frequency, degree, level of certainty, etc., Answering questions such as how?, in what way?, when?, where?, and to what extent?.

Examples of adverbs in English include gently, here, now, very.

Adverbs are usually considered to be a part of speech

- affix

An affix is an addition to the base form or stem of a word in order to modify its meaning or create a new word. An affix is a morpheme which can attach before (as a prefix), after (as a suffix), inside (as an infix), or around (as a circumfix) the stem or base form of a word.

The following chart gives examples of different kinds of affixes in English and in Kunwinjku:

AFFIX ENGLISH EXAMPLE KUNWINJKU EXAMPLE SCHEMA DESCRIPTION Prefix un-do Ngalwamud (female of Wamud skin) prefix-stem Appears before the stem Suffix look-ing Sydney-beh (from Sydney stem-suffix Appears after the stem Infix abso〈flippin’〉lutely kamre (he/she is coming – compare kare he/she is going) st〈infix〉em Appears within a stem Circumfix en⟩light⟨en xxx circumfix⟩stem⟨circumfix One portion appears before the stem, the other after - alveolar ridge

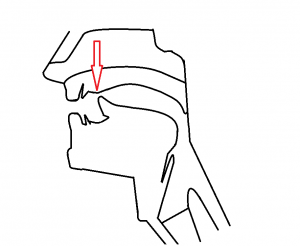

The alveolar ridge is a hard ridge found just behind the upper teeth.

Many consonant sounds are made with the tongue making contact with the alveolar ridge, such as [d, n, t, l].

To feel your alveolar ridge, put your tongue on your top teeth then pull it back along until it touches the roof of your mouth (palate). You should feel a ridge between your teeth and the palate.

Retroflex sounds are made at the alveolar ridge also, but use the underside of the tongue to make contact. - article

An article is a word used to refer to a noun.

English uses two kinds of articles:

- definite article – the

- indefinite article – a, an

Technically these are part of the word class known as determiners

Australian languages do not generally use articles, but have a range of determiners.

- circumfix

An affix that attaches around a stem.

For example in English en-light-en – the two parts of the affix go together and surround the stem.

- clause

A clause is the next smallest unit after a sentence, it generally includes a subject and a verb.

After they cooked dinner, they ate it. Contains 2 clauses:

After they cooked dinner, and they ate it.

- conjugation

Conjugation is the change that takes place in a verb to express tense, mood, person, etc. The term is commonly used for verbs which in many languages can be classified according to the shape of the affixes endings they may take to indicate different things.

An example in English shows how the verb break is conjugated:

Present Simple

I, You, We, They: break

He, She, It: breaksPresent Continuous (Progressive)

I: am breaking

You, We, They: are breaking

He, She, It: is breakingPresent Perfect

I, You, We, They: have broken

He, She, It: has brokenPast Simple

I, You, We, They, He, She, It: broke

Past Continuous

I, He, She, It: was breaking

You, We, They: were breakingPast Perfect

I, You, We, They, He, She, It: had broken

Conjugation can indicate person, number, tense, aspect, mood, voice or other grammatical information, often represented morphologically on the verb.

- conjunction

A conjunction is a part of speech that is used to connect words, phrases, or sentences.

Examples in English include: but, and, as, because, so, yet etc.

Conjunctions connect thoughts, actions, and ideas as well as nouns, phrases and other parts of speech, e.g., John came to work early and finished late.

They are useful for making lists, e.g., I would like juice, coffee and a muffin please.

Conjunctions must agree, e.g., Sarah was tired yet she went to sleep, does not show agreement. Sarah was tired so she went to sleep, does show agreement.

- consonant

A consonant is a speech sound made with some closure or constriction of the vocal tract.

Examples are [p], pronounced with the lips; [d], pronounced with the front of the tongue; [k], pronounced with the back of the tongue; [m] and [n], which have air flowing through the nose (nasals). Contrasting with consonants are vowels.

- demonstrative

Demonstrative words show which person or thing is being referred to.

They specify an entity in terms of the distance (real or metaphorical) from the speaker (e.g. this week, those books)

Examples of demonstratives in English include this, that, these, those.

There is a distinction between demonstrative adjectives, which modify nouns, and demonstrative pronouns, which replace nouns

- These pretzels are making me thirsty (demonstrative adjective)

- I don’t like this book (demonstrative adjective)

- That smells delicious (demonstrative pronoun)

- Those are my favourites (demonstrative pronoun)

Australian Aboriginal Languages make finer distinctions in demonstratives than English does. They generally express distances in space and time, and may indicate things such as

- distance from the speaker or hearer

- here, close by

- here, a little further

- there, close by

- there, some distance

- there, out of sight

- there, a long way away

- place in discourse

- that mentioned just now

- that mentioned before

- assumptions about the hearer’s attention

- the one being pointed to

- the one just mentioned

- the one you know is being referred to

Demonstratives may be marked for person and number

- Demonstrative pronouns might have an object form in your Language.

- Demonstratives might have dual and plural forms.

Demonstratives might also be marked for person and number, e.g.

- those two, nearby

- that female, far away

- dental

A consonant sound made by touching the tongue to the top teeth. Examples include [t], [d],and [n] in English.

- determiner

A Determiner is a word, phrase or affix which modifies a noun phrase.

In English they can also be articles, possessive pronouns, and numerals.

- dialect

A variety of a language, that has derived from another language. Despite some differences in pronunciation, vocabulary usage etc., dialects are often mutually intelligible.

E.g., Australian English is a dialect of British English.

- diphthong

A diphthong is a sound made by combining two vowels in the same syllable, specifically when it starts as one vowel sound and goes to another.

English has examples such as in joy/join, cow/count, my/mind, say/safe.

Diphthongs refer to vowel sounds, not letters (combinations of two letters are called digraphs). Don’t be confused by spelling – some English words have two vowel letters which don’t represent a diphthong (eg head, four), while others have a single vowel representing a diphthong.

Many Aboriginal languages have diphthongs, which may be represented in spelling by a vowel with either y or w.

e.g., Kunwinjku: ruy (cooked), rowk (all)

Yolngu matha: yow (yes), bäy’ (leave behind)

- dual

While many languages distinguish between singular (for one) and plural (more than one), some languages also use a specific form for ‘two and only two.’ When a noun or pronoun appears in dual form, it is interpreted as referring to precisely two of the objects or persons identified by the noun or pronoun. Verbs can also have dual forms in these languages.

- fricative

A consonant sound made by bringing two places of articulation close together but not closed, so that the passing air through this space creates enough turbulence to create sound. Some examples in English are [s], [f], and [v].

- gender

Some languages make a distinction based on gender when classifying nouns.

For example in English there are masculine, feminine and neutral gender pronouns – he (MASC), she (FEM) and it (NEUTRAL).

Other languages such as Spanish use gender for all nouns – for example in Spanish a woman is feminine, but so is a hen and a table.

This is grammatical gender, and has nothing to do with with natural sex distinctions.

Indigenous languages vary in their use of gender, so you need to learn the rules specific to the language you are learning.

In Kunwinjku, masculine and feminine are used for people and other nouns, and there are other noun classes for other groups of nouns.

- glottal stop

The glottis is the space between the vocal cords, and when this is blocked (or stopped), a glottal stop is produced.

It can be hard for English speakers to identify this sound, despite the fact that it is quite common in English, often used to replace a ‘t’ sound in words like ‘football’ or ‘not yet’. It is stereotypically characteristic of Cockney English words like ‘bottle’. It is also used in expressions like ‘uh oh!’

While in English this sound doesn’t change the meaning of any words, in many languages it does. For example in Kunwinjku (where this sound is spelled ‘h’):

- ngare = I go, I will go

- ngahre = I am going

- grammar

Grammar is the system and structure of a language or of languages in general. In other words, it’s the collection of principles defining how to put together a sentence.

A common contemporary definition of grammar is the underlying structure of a language that any native speaker of that language knows intuitively. The systematic description of the features of a language is also a grammar. These features include the system of word formation (morphology), the ways in which words can be ordered to create meaning (word order, also referred to as syntax), which are the main focus of grammar. Some definitions of grammar also include the sound system phonology (phonology),and how words create meaning (called semantics).

- imperative

The imperative mood refers to the use of verb structures in a direct or commanding manner. It is often used when signalling to another person a directive, a dangerous situation, or an emotional expression, e.g., aggression.

In English the imperative is often signalled in writing with the use of an exclamation mark. E.g., Come here! Stop! Don’t do that!

- imperfective

The imperfective is used in language to describe ongoing, habitual, repeated, or similar semantic roles, whether that situation occurs in the past, present, or future. A verb form or aspect which expresses action as incomplete or without reference to completion or as reiterated — compare perfective.

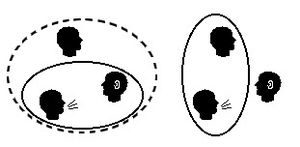

- inclusive/exclusive

In English, if you hear someone say “We’re going to a party,” how do you know if you are going to the party or not? In English you would have to add something like:

- “We’re going to a party. Would you like to come?”

- OR

- “We’re going to a party. Are you bringing a present?”

In many languages, a different form of the ‘we’ pronoun can be used to indicate if the person being spoken to (the addressee, or the ‘you’ implicit in the sentence) is included or excluded.

The inclusive form of the pronoun means the speaker and the addressee(s). The exclusive form of the pronoun means the speaker and someone else but not the addressee(s).

In the above example, the first ‘we’ would be exclusive, and the second would be inclusive.

This is a really useful grammatical distinction (which would probably be very helpful in English!), but might take some time to learn how to understand and use it correctly.

Some languages also distinguish how many people are involved in the ‘we’, with different words for dual, trial and plural.

LEFT: Inclusive RIGHT: Exclusive

- infix

See affix.

- interjection

An interjection is a word or expression which occurs on its own, expressing a spontaneous feeling or reaction.

Examples in English include: hey, bye, ouch, um, er, huh? okay, yeah etc.

- intonation

Intonation uses changes in the pitch of the voice to convey meaning.

Intonation carries information that is not provided by the stream of consonants and vowels. It might tell the listener whether the sentence is a question or a statement, or whether more will follow. Intonation may also signal differences in meaning or in attitude.

More technically, it is the part of the sound system of a language which involves the use of pitch to convey information. It consists of both accent (concerns individual words) and sentence melody (concerns word groups).

- intransitive

Verbs which can never have an object are called INTRANSITIVE – examples include sleep, die, go, cry, laugh, fall. In these cases, the action of the verb doesn’t affect anyone, it just happens. E.g.,

- I sleep

- He cries

- We go

- It died

- They fell

In English some verbs can either take an object (e.g., she ate meat) or not (she ate), but in many languages, you couldn’t just say she ate, you would have to specify what she ate. So don’t assume that transitivity works the same way in the language you’re learning as it does in English.

- irrealis

Irrealis mood is used to indicate that a certain situation or action is not known to have happened as the speaker is talking. It’s a way of expressing an event or thing that is non-actual, or non-factual at the time that the speaker is telling it.

For example, irrealis is used to express things that haven’t happened, nearly happened, won’t happen, might happen, might not happen, or we wish they’d happen.

English doesn’t have a single way of expressing this, but many Australian Indigenous languages do. Some examples in English of sentences that may use an irrealis form in an Indigenous language:

- If I had been there then I would have….

- I didn’t see the dog

- You should have gone

- He probably went home

- I wish it would rain

- She might get sick

Note that all these sentences refer to situations that have not happened, they’re not currently ‘real’, consequently ‘irrealis’

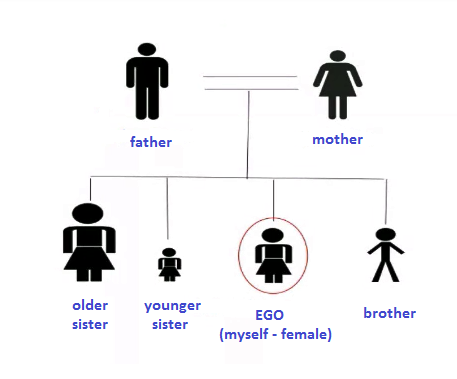

- kinship

The term ‘kinship’ is used to describe family relations, the connections between people usually based on bloodlines or marriage. Kinship systems vary across cultures and within Australian Indigenous groups there are many similarities and differences.

Kinship is often represented using family trees – below is a very simple one showing a female and her siblings and parents, with the English terms provided.

More information is available online about kinship in Australian Indigenous groups, for example the University of Sydney has an excellent online course exploring these concepts at http://sydney.edu.au/kinship-module/

- loanword

A loanword is a word which has been adopted from another language.

An English we have many loanwords. E.g., pizza (from Italian), restaurant (from French), kindergarten (from German), safari (from Swahili), avatar (from Sanskrit), ketchup (from Hokkien), futon (from Japanese).

Often loanwords are integrated into the sound system of the language they’re being borrowed into – for example, we don’t use the French pronunciation of restaurant when we use the word in English.

All languages borrow words from other languages.

Aboriginal languages use loanwords from other Aboriginal languages or from English. Some languages of the Top End of Australia have borrowed words from Indonesian from the time of trade with Macassans, such as djurra (or djorra) for book or paper, and rupia for money.

See here for a list of words from Queensland languages.

- locative

A locative marker indicates the location of something.

In English, this is often done using a preposition such as at, to in, etc., but in many Aboriginal languages it is done by adding a morpheme to the noun.

- moiety

Moieties are two social or ritual groups into which a people is divided.

Everything in the Bininj world view is made up of two moieties, Yirridjdja and Duwa. These are two halves of a holistic world view. Everything in the world, the countryside, nature and society is known to be of one, or the other (never both).

A man and his offspring are in one of these moieties, his wife and her siblings and their father are in the other. These have strong influences over ceremonial and relational activities and interactions.

Yirridjdja and Duwa are patrimoieties, passed down from the father’s line. Some groups also have matrimoieties, which are passed down through the mother. All Bininj belong to either the Ngarradjku or Mardku matrimoiety, and these affect marriage rules.

- morpheme

The morpheme is the smallest meaningful unit in a language.

E.g., I English unbelievable can be broken down into 3 separate morphemes or meaningful parts of speech.

un-believe-able

un– and –able are both affixes, and believe is the rootof the word.

Each morpheme contributes meaning to the whole.

- morphology

Morphology is all about the meaningful parts of words that go together. These are called morphemes.

A typical way that morphology is shown, is through affixes, small units of meaning that attach to a word (or technically around a stem, which may or may not be a word in itself). The most common types of affix are prefixes that go at the beginning, and suffixes which go at the end, though some languages have infixes which go inside a word or circumfixes which go around a word.

See the entry for affix for examples of these.

- nasal

Nasal sounds are produced by blocking the air in the mouth and allowing it to resonate through the nose. Nasal sounds are consonants and almost always involve voicing.

Examples of nasals include m, n, ng, which are common in English.

Australian Indigenous languages often have more nasal consonant sounds than English, including a retroflex nasal (written either rn or ṉ) and a palatal (usually written either nj or ny).

- noun

A noun is a word that functions as the name of some specific thing or set of things, such as living creatures, objects, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, or ideas.

A noun is a part of speech that can occur as the main word in the subject of a clause, the object of a verb, or the object of a preposition. They can be modified using an adjective or an adjective phrase.

In some languages, nouns can be grouped together in a noun class . They can often be marked for number (e.g., singular and plural)

- noun class

A noun class is a particular category of nouns. A noun may belong to a given class because of characteristic features of its referent, such as sex/gender, animacy, shape, but sometimes there doesn’t seem to be any pattern linking words in a particular class.

Many European languages use gender (e.g., French has masculine and feminine, while German and Russian have masculine, feminine and neuter), while some African languages have many different noun classes (for example Swahili has up to 18 different classes, for example for people, plants, etc., but some groups seem to have no meaning in common).

Noun classes tend to ‘agree’, for example feminine nouns in French take the feminine form of adjectives and possessives (eg la grande table, whereas masculine le grand livre). There are many objects in these noun classes that we would not often think of as ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’. In Swahili, the noun class is shown on the noun and the adjective (e.g., mtu mzuri (good person) and watu wazuri (good people)).

Some Australian Indigenous languages have noun classes, including Kunwinjku, which has four classes, marked by different prefixes:

- na- ‘masculine’

- ngal- ‘feminine’

- kun- ‘other’

- man- ‘vegetal’

- noun phrase

A noun phrase is a phrase which has a noun as its core component. It can have an adjective, determiner, or pronoun in the phrase as well, but it does not include a verb.

E.g., The Cat, A big mountain, His jacket, One apple.

- number

Number is a grammatical category of nouns, pronouns, and verb agreement that expresses how many.

English distinguishes between one (singular) and more than one (plural). Many Australian languages have words to indicate two (dual), and sometimes three (trial).

English sometimes uses dual and trial, in words like twice and thrice or both, but it’s much more common in Australian Indigenous languages.

- numeral

A numeral is a word which is often an adjective or pronoun that expresses a number.

It also shows the relationship between the number and the word which is expresses.

E.g., The tenth street, by the dozen, a pair of shoes, first, second, third.

- object

The object of a sentence is the entity (represented by a noun) which is affected by the action (represented by a verb).

Objects can be either of two types:

- direct object – an item in a sentence which indicates the thing or being which is immediately affected by the action of the verb

- eg. he bought a book, she saw the boy

- note that the effect on the object may not be tangible – in these example sentences, the book is affected by the person buying it, while the boy is not affected by the person seeing him

- Direct objects follow transitive verbs

- indirect object – an item in a sentence which accompanies the direct object and which frequently denotes the person or thing affected by an action

- eg She wrote a letter to her cousin; She gave him the book.

-

For an indirect object to appear, a sentence normally already has a direct object.

- In English, indirect objects are normally indicated by the word to or the form of the pronoun

- direct object – an item in a sentence which indicates the thing or being which is immediately affected by the action of the verb

- orthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language. It includes rules of spelling, hyphenation, capitalisation, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Some languages use an alphabetic system, such as the Roman system (used for English and all Australian Indigenous languages) or the Cyrillic system (used for Russian). Other types of orthography include syllabic where each symbol represents a syllable (used for Japanese) and logographic, where each syllable represents a concept (used for Chinese)

Orthography is distinct from grammar, which concerns the structure of languages and not their writing.

- palatal

The palate in humans is the hard part of the roof of the mouth. A palatal consonant refers to a speech sound which is made by some sort of contact with the palate of the mouth.

One of the most common palatal consonants is [j].

- part of speech

Words are grouped together according to their function in language. Parts of speech are categories of (grammatical) words that ‘do’ different things in a phrase or sentence. They are sometimes referred to as word classes.

Commonly listed parts of speech are noun, verb, adjective , adverb , pronoun , preposition, conjunction, interjection, and sometimes numeral, article or determiner.

Not all languages have the same parts of speech, and in each language, the same part of speech can do different things. Identifying parts of speech gives an idea about what words are going to do what in a phrase or sentence.

Parts of speech are sometimes referred to as grammatical categories.

- perfective

When used to talk about verbs the perfective is used in expressing action as complete or as implying the notion of completion, conclusion, or result. The perfective aspect indicates that an action, situation, or event is seen as complete at a particular time.

- person

This refers to the actors in a specific phrase.

I.e. Who is doing something in the phrase. In English you can have 1st person (I/me), 2nd person (you) , and 3rd person (he/she/it).

Person can also have gender (eg male and female) and number (eg singular for one person, dual for two people, trial for three people, and plural for more than three people.

Some languages also show differences when a (non-singular) person is inclusiveexclusive.

There are other possibilities, such as whether the ‘person’ is human or non-human, animate or inanimate, etc.

An English phrase such as “you see him” is ambiguous, as ‘you’ can be singular or plural, but this phrase can be parsed in the singular as 2sg – SEE – 3sg.

- phoneme

A phoneme is the smallest contrastive sound unit in a language.

A phoneme is usually represented by a single letter or symbol in a language, however it can be pronounced in a number of ways without changing the meaning.

For example the phoneme /s/ in English can be used to form plurals.

While it always spelt with an /s/ it is not always pronounced the same way.

Consider dogs, and cats.

The /s/ after the word dog is actually pronounced like a [z] sound while after cat it has the more typical [s].

- phonology

All languages follow a specific set of rules that determine how we sound when speaking. The study of these rules is called phonology.

One of the main focuses in phonology is contrast – which sounds can create a change in the meaning of a word? For example in English, the words ‘cap’ and ‘gap’ have different meanings, so the sounds [k] and [g] must be distinct phonemes. In many Aboriginal languages, there is no distinction between [k] and [g], they are the same phoneme (so are usually represented by a single letter, either ‘k’ or ‘g’).

The test for a phoneme in a language is to find two words which are identical in every respect except for one sound. The word will change in meaning depending on which of the two differing sounds is used.

Writing systems in Aboriginal languages (as in many other languages) are based on the phonological system of the language, with a separate symbol (or letter) for each sound (or phoneme). The English writing system is partly phonological, but has some symbols (such as ‘th’) that represent different sounds (think about the initial sounds in the words thin and then), and some sounds (such as [f]) which can be represented by different symbols (think about words like fun, laugh, phone, coffee).

- plural

Plural is normally contrasted with singular, where singular is ‘one’ and plural is ‘more than one’. This is how it works in English, however in languages which have dual or trial or other forms, then plural may mean ‘more than two’ or ‘more than three’.

- possessive

A possessive form (abbreviated POSS) is a word or grammatical construction used to indicate a relationship of possession in a broad sense, which might be ownership (e.g., my car) or a similar concept.

In English, possession can be indicated using a possessive pronoun such as my, your, our, their, or by the possessive suffix ‘s.

- My head hurts

- John‘s car is red – note that the possessive marker is on the noun of the one who possesses the thing.

- That book is yours

Indigenous Australian languages may use different ways to indicate possession. Some languages distinguish between things which cannot be separated from their owner, such as body parts – this is called inalienable possession. These would be marked with different forms than things which can be separated from their owner – consider the difference between your head and your book.

Note that the term genitive is often used to discuss possession.

- postposition

See preposition.

- prefix

A prefix is an affix which is placed before the stem of a word.

Some languages allow multiple prefixes before a stem , for example in English the word unenforceable consists of two prefixes, a root, and a suffix:

un- en- force -able PREFIX- PREFIX- ROOT -SUFFIX Some prefixes change depending on the root, for example in English in- becomes im- before certain roots:

insecure, incapable, inaccurate but immovable, impatient.

In some languages, hyphens are used to show how words are broken up into different morphemes.

- preposition

A grammatical word which occurs with a noun or phrase to express the relation it has to other parts of a sentence.

Prepositions are essential to sentences because they provide additional and necessary details, such as where something takes place (such as at the shop), when or why something takes place (such as before dinner), or general descriptive information (such as the man with the broken leg).Prepositions go ‘before’ the thing they modify (usually a noun or a noun phrase) – in some languages these go after the thing, and are called postpositions.In some languages prepositions are separate words, where as, in others they attach to the word they refer to.In English prepositions can be presented as a prepositional phrase, such as on top of, or in between. - pronominal prefix

This prefix identifies the subject of the verb by a pronoun.

In Bininj Kunwok, these are a compulsory part of the verb phrase (except for 3rd person in past tense constructions).

The following chart shows the full range of pronominal prefixes alongside the independent pronouns that are sometimes used for emphasis:

SUBJECT (intr)

INDEPENDENT

ENGLISH

1st person

SINGULAR

nga-

ngaye

I, me

DUAL INC

ngarr-

ngarrku

I + you

DUAL EXC

ngane-

ngarrewoneng

I + 1 other (not you)

TRIAL INC

kane-

karrewoneng

I + you, and 1 other

PLURAL INC

karri-

kadberre

I + you and others (3+)

PLURAL EXC

ngarri-

ngadberre

I + 2+ others (not you)

2nd

SG

yi-

ngudda

you (1)

DUAL

ngune-

ngurrewoneng

you (2)

PLURAL

ngurri-

ngudberre

you (3+)

3rd

SG MASC

ka-

nungka

he, him

SG FEM

ka-

ngaleng

she, her

DUAL

kabene-

berrewoneng

they 2

PLURAL

kabirri-

bedda

they 3+

- pronoun

Pronouns are used in place of nouns. Instead of saying:

- John went to John’s mother’s house with John’s brother and John’s wife to see John’s grandparents.

we say:

- John went to his mother’s house with his brother and his wife.

If we continued telling the story we could then say:

- He went with them and saw them there.

Words like you, him, they, our, etc. are called pronouns. All languages use pronouns, but often they use them differently to how they’re used in English.

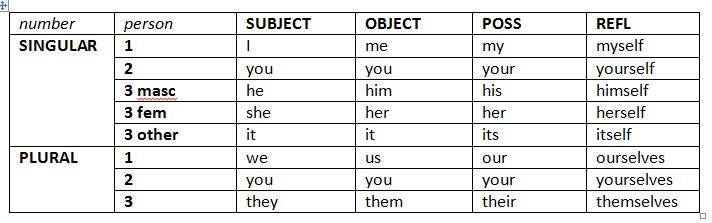

It’s helpful to use different terms to identify these pronouns, rather than just using English words. The following chart lays out the English pronoun system, which distinguishes by person (1st, 2nd, 3rd), number (singular, plural) and case ( subject , object , possessive & reflexive ).

The ‘first’ person is the person who is speaking – in English ‘I’ or ‘me’ (1sg), or in plural form ‘we’ or ‘us’ (1pl).

The ‘second’ person is the person being spoken to – in English ‘you’ (note that in English it is the same whether it is one person (2sg) or more (2pl) being spoken to.).

The ‘third’ person is the person being spoken about – in English it’s necessary to show if it’s male or female, or something without gender (neuter) – ‘he’, ‘she’, or ‘it’ / ‘him’, ‘her’, ‘it’ (3sg) – and in plural form ‘they’ or ‘them’ (3pl).

Notice how there are different forms of the pronoun depending on whether it’s the subject, the object, the possessive (belonging to) or the reflexive form (doing something to oneself).

So now we can talk about pronouns by using their function rather than an English term – e.g., 3sg-FEM-SUBJ to describe she (third person singular feminine subject), and 2pl-POSS to describe your (second person plural possessive).

NOTE: Not all languages make the same distinctions – in many Aboriginal languages (including Bininj Kunwok), there is only one form of the third person, it doesn’t matter if they’re male or female, human or other, it’s all the same form. They often use different systems of number, where a different word (or morpheme

) is used if there are two things involved (called dual) or three things (called trial), or more things (called plural). Note that depending on the language, plural might mean ‘more than one’ (like in English) or ‘more than two’ (if a language has dual but not trial forms) or ‘more than three’ (like Kunwinjku).

A reciprocal construction refers to an action involving two or more subjects which affects both participants.

E.g., They hit each other, They yelled at each other, They appreciate each other, They care for one another.

A process in which part of the root or stem of a word is repeated.

This is a common process in Australian languages, and is sometimes used to mean ‘many’

eg. wagga crow (Wiradjuri)

Wagga Wagga (place name meaning place of many crows)

Reflexives indicate that the subject and object are the same

Reflexive pronouns are commonly used in languages, for example in English:

- He washed himself

- She looked at herself

- They dressed themselves

A pronoun which refers to the relative clause in a sentence.

E.g., The woman who worked here.

Retroflex sounds are made by curling the tongue back so that the underside of the tongue touches the area just behind the teeth (the alveolar ridge).

Sounds like [n], [d], and [l] are normally made with the tongue tip touching the alveolar ridge, but retroflex sounds use the underside of the tongue touching the same place.

Retroflex sounds have a ‘rhotic’ quality – like an ‘r’ sound.

These can be difficult for speakers of Australian English, who tend to ignore ‘r’ sounds before consonants. It’s important to make these sounds as retroflex, as you might be saying a completely different word if you don’t curl your tongue back.

Retroflexes are very common in Australian Indigenous languages, but they can be spelled in different ways. For example, Yolngu matha uses underscored letters: ḻuku, maṉḏa, waṯu, as does Pitjantjatajra: Kata Tjuṯa, Aṉangu, while Bininj Kunwok and Warlpiri use a digraph such as wurdurd (children – K), warna (snake – W).

The morpheme in a word which carries the main meaning, and to which affixes attach.

Singular refers to a word form that has one and only one referent, meaning it refers to one person, place, thing, or instance.

Singular is usually contrasted with plural, but in some languages also contrasts with dual (two) and sometimes trial (three).

For example: In English ‘I’ is the 1st person singular form of ‘to be’. ‘We’ is the plural form. In English we only contrast between singular and plural, but other languages (in particular Australian Indigenous languages) may also contrast between ‘we two’, ‘we three’, ‘we but not you’ and more.

The singular form may be indicated on a noun, verb, adjective or other part of speech, or sometimes left unmarked, with the non-singular forms showing the contrast.

A stem is either a root, or a root with an affix attached.

Other inflectional affixes can attach to this stem.

For example in English, tie and untie are both stems. They can both have inflectional affixes attached to change their meaning, such as ties or untied.

A stop is a type of consonant which is formed by stopping the air completely in the mouth (e.g., by closing the lips or blocking the air with the tongue at the alveolar ridge, then releasing it suddenly. The release is sometimes accompanied by a puff of air (called aspiration).

Stops are sometimes called plosives – they mean the same thing, but stop focuses on the stopping part, plosive focuses on the release.

The most common stops are [p, b, t, d, k, g] plus retroflex stops [rd, rt] and glottal stops. Nasal sounds (like [m, n, ng, ny]) are sometimes called nasal stops, as they also block the air completely in the mouth, but don’t release in the same way as oral stops.

Stops can be voiced or voiceless (see voicing) but in many Aboriginal languages this doesn’t change the meaning.

The subject of a sentence is the person, place, thing, or idea that is doing or being something. You can find the subject of a sentence if you can find the verb. Ask the question, “Who or what ‘verbs’ or ‘verbed’?” and the answer to that question is the subject.

E.g., The horse gallops across the field.

What is the verb? Gallop. Who gallops? The horse. Therefore The horse is the subject.

The subject is a noun, a pronoun or a noun phrase.

The subject in each of these sentences is in italics:

- The cat sat on the mat

- John likes Mary

- She is a vegan

- Yesterday a large green tree frog jumped into the river

- Three men, two women, four kids and a dog went hunting.

- My grandmother’s old house was very small.

A suffix is an affix which is placed after the root of a word.

Some languages allow multiple affixes after a root, for example in English the word unforeseeability consists of a prefix, a (compound) root, and two suffixes:

| un- | fore-see | abil | -ity |

| PREFIX- | ROOT | SUFFIX | -SUFFIX |

In some languages, hyphens are used to show how words are broken up into different morphemes.

A syllable is a measurement of the vowel sounds in a word.

However many seperate vowel sounds you can hear, signifies the number of syllables.

You can hear these best by saying them out loud:

E.g., cat: cat (1 syllable), pepper: pepp-er (2 syllables), element: el-e-ment (3 syllables).

A reference to the point in time at which an action takes place from the perspective of the speaker.

Three common tenses which are frequently distinguished are

- past – happened at some time before the current time of speaking

- present – happening at the time of speaking

- future – not yet happened at the time of speaking

Many languages use different forms of the verb depending on the tense

- e.g. English – I saw (past), I see (present), I will see (future)

Australian Indigenous languages may indicate tense in different ways, and may have different ways of splitting up time, such as remote past or a distant future.

Tense is sometimes considered in contrast or comparison with aspect and mood.

Verbs which must always have an object are called TRANSITIVE – examples include hit, see, want, carry etc. In these cases, the action of the verb has some effect on someone or something else.

Look at the following two English sentences:

a) the dog chased the cat

b) the cat chased the dog

In the above example, ‘chased’ is a verb that needs both a subject and an object. In English we can’t just say ‘the dog chased’, we have to say who or what it chased. There are lots of verbs like this, e.g.,

- The girl saw the boy

- The cow broke the fence

- I love you

- He wants ice-cream

- The car hit the curb

Other verbs only have a subject and can’t have an object, these are called intransitive verbs.

An example of an intransitive verb is ‘sleep’ e.g., you can’t say *’the man sleeps the dog’. You can say ‘the man sleeps’ or ‘the dog sleeps’.

Note: In many Aboriginal languages, whether a verb is transitive or intransitive will affect how that verb works in a sentence.

In linguistics, transitivity is a property of verbs that relates to whether a verb can take direct objects and how many such objects a verb can take.

E.g., A transitive verb means that the verb needs a direct object to make sense.

I.e., She hit the boy – you cannot say just *she hit because the verb requires something ‘to hit’. Other common English verbs which are transitive include, give, see, like, hear, receive, watch, love, etc.

An intransitive verb, instead does not require a direct object for the phrase to be complete. E.g., She sleeps, He sneezed, They sit, The dog ran. etc.

Different languages can distinguish between singular (for one), dual (for two) and plural (more than one/two), some languages also use a specific form for ‘three and only three’ When a noun or pronoun appears in trial form, it is interpreted as referring to precisely three of the objects or persons identified by the noun or pronoun.

No language has a trial number unless it has a dual.

A term used in sociolinguistics to talk about specific language groups.

A different variety of a language may involve different vocabulary or pronunciation for example, or be spoken by members of a particular sub-group.

A variety of a language may include dialects. It’s a helpful term that avoids having to specify if a language is a distinct language or a dialect or how it’s related to another language.

A word used to describe an action, state, or occurrence, such as run, hear, become, happen.

Verbs may be transitive or intransitive – see Transitivity

A phrase which has a verb as its main component.

E.g., The dog chased the cat.

Voicing is determined by vibration of the vocal cords during the production of a single sound. If the vocal cords are vibrating, that sound is considered voiced. If they’re not vibrating, that sound is considered voiceless.

To feel this, put your hand on your throat and touch your Adam’s apple, and make the sounds [sssss] and [zzzzz]. You should feel vibration of your vocal cords during [z] but not during [s].

All sounds are either voiced or voiceless, and some pairs of sounds are identical in how they’re produced except for the voicing (such as [s] and [z] but also [f] and [v] and many other pairs). If the contrast in voicing is enough to change the meaning of the word, then these sounds are considered to be separate phonemes (see phonology.

In many Aboriginal languages, there is no voicing contrast. This means that speakers of these languages consider pairs of sounds as the same phoneme. For example, in Kunwinjku, [k] and [g] don’t change the meaning of any word, so they’re considered the same sound (which is why there’s a k but no g in the Kunwinjku alphabet), however the different sounds do tend to occur in different positions in the word.

Vowels are speech sounds made with no closure or constriction of the air flowing through the vocal tract. In contrast to consonants, in vowels the tongue does not touch the lips, teeth, or roof of the mouth. Different vowel sounds can be made by moving the tongue up, down, front or back within the vowel space (without touching anywhere) and rounding or spreading the lips.

Vowel sounds are often represented in a language’s orthography in an alphabetic system by the letters A, E, I, O, U and combinations of these.

While English uses these 5 letters, there are around 20 different vowel sounds in Australian English. Many languages (including Kunwinjku) only have 5 vowel sounds.

In English, word order is an important way of showing who did what to who. For example, compare these two sentences:

a) the dog bit the man

b) the man bit the dog

Changing the order of the words changes the meaning drastically. English uses the word order SUBJECT – VERB – OBJECT, which means that in sentence a) ‘the dog’ is the subject and ‘the man’ is the object, and we know that the dog is the one doing something (in this case, biting) to the man. In sentence b) the fact that ‘the man’ comes before the verb means it’s the subject of the sentence, and is the one doing the action to the one after the verb.

In many Aboriginal languages, word order doesn’t have the same function. Instead, there may be something attached to a word to show who is the subject, or who is the object. While no language has completely ‘free’ word order, languages differ in how word order affects meaning.

In Kunwinjku, word order doesn’t matter in the same way as in English.

- Duruk bibayeng bininj

- Bininj bibayeng duruk

Both these sentences mean “the dog bit the man” despite word order. In Kunwinjku a prefix on the verb specifies who did it to whom. So regardless of word order, we know who did the biting. Duruk is still the subject, whether it’s before or after the verb, and bininj is still the object, no matter where it is in the sentence.